DUBAI: Groundwater levels are in significant decline around the world, particularly in agricultural regions with dry climates that experience severe water deficiency. Saudi Arabia is one of several Middle Eastern nations that struggle with water scarcity.

The Kingdom is among the most arid countries in the world due to its minimal rainfall and high evaporation rates. Its climate exposes it to temperature fluctuations, little annual precipitation, no natural perennial flow, and few groundwater supplies.

However, over the last few years, especially within the Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture, work has been done to stabilize and even recover Saudi Arabia’s groundwater levels as well as develop plans to maintain the nation’s water resources at a sustainable level.

Due to the discovery of lucrative fossil fuels around four decades ago, the Kingdom has experienced an exceptional period of economic growth and is rapidly transforming its economy and society further under Vision 2030, launched in 2016 by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

FASTFACT

-

World Water Day is an annual UN observance day held on March 22 that highlights the importance of freshwater.

Saudi Arabia’s economic boom has resulted in a higher standard of living for its people as well as large-scale urban migration and an increase in population growth. The country grew from 4 million in 1960 to around 36.9 million in 2022, according to the General Authority for Statistics, also known as GASTAT.

The Kingdom is now, according to GASTAT, the 41st most populous country in the world.

While Saudi Arabia’s economic boom, increased opportunities, and population growth are positive gains for the country on its road to socio-economic transformation, such successes have also placed the country’s scarce water resources under extreme pressure.

Presently, the Kingdom relies on three basic sources for water extraction: Desalinated seawater, groundwater, and recycled water regularly used in electricity production.

Saudi Arabia derives some of its water from the sea. This is done through the process of desalination, which involves transforming brackish seawater into potable water. The Kingdom is now officially the world’s largest producer of desalinated water.

A view of the Jubail Desalination Plant at the Jubail Industrial City in Saudi Arabia's Eastern Province overlooking the Arabian Gulf. (AFP)

Groundwater aquifers, both renewable and non-renewable, are considered the most important resource for freshwater in the Kingdom. Aquifers in Saudi Arabia supply more than 90 percent of the agricultural sector’s water needs and around 35 percent of urban water needs.

“Actions are being taken but more are needed,” Saleh bin Dakhil, a spokesperson for MEWA, told Arab News. “Saudi Arabia is spearheading initiatives locally to mitigate the impact of high water demand mostly to agriculture.”

Aquifers have long been a major source of water in Saudi Arabia and comprise vast underground reservoirs of water.

During the 1970s, the government undertook a major effort to locate and map such aquifers and estimate their capacity. It then drilled tens of thousands of deep tube wells in areas with the most potential for both urban and agricultural use.

In the oases of Al-Ahsa in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, scientists have found that traditional farming techniques stretching back centuries helped preserve one of the region’s green gems. (Supplied)

“Groundwater is a critical resource for irrigated agriculture, livestock farming and other agricultural activities, including food processing,” Jippe Hoogeveen, senior land and water officer in the Land and Water Division at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, told Arab News.

“In order to meet global water and agricultural demands by 2050, including an estimated 50 percent increase in food, feed and biofuel demand relative to 2012 levels, it is of critical importance to increase agricultural productivity through the sustainable intensification of groundwater abstraction, while decreasing the water and environmental footprints of agricultural production.”

Where a perennial and reliable source of shallow groundwater exists, groundwater can be an important source for smallholder farmers, said Hoogeveen.

Over the last few years, especially within the Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture, work has been done to stabilize and even recover Saudi Arabia’s groundwater levels, as well as develop plans to maintain the nation’s water resources at a sustainable level. (Shutterstock)

Regions heavily reliant on groundwater for irrigation include North America and South Asia, where 59 percent and 57 percent of the areas equipped for irrigation use groundwater, respectively.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, where the opportunities offered by the vast shallow aquifers remain largely underexploited, only 5 percent of the area equipped for irrigation uses groundwater.

Saudi Arabia’s water shortage impacts sustainable agriculture, industrial development and the well-being of the population.

The Kingdom uses 80 percent of its water for agricultural purposes, with groundwater extraction accounting for most of this demand, which is not sustainable, according to a 2023 research paper titled: “Water Scarcity Management to Ensure Food Scarcity through Sustainable Resources Management in Saudi Arabia.”

The Kingdom has launched its National Water Strategy 2030, which has been prepared according to the principles of integrated water resource management and aims to restructure the country’s water sector and transform it into a more sustainable and efficient one. (MEWA photo)

Another three-year study by researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in the US shows that groundwater is declining around the world. It found that groundwater is dropping rapidly in more than two-thirds of the aquifers, or 71 percent, of 1,700 aquifers studied — three times as many as expected.

Having declined in the 1980s and 1990s, depletion rates have since sped up in the last two decades. In some countries, such as Iran, groundwater decline is widespread. But in parts of Saudi Arabia, groundwater levels have stabilized or even recovered, the report found.

The report demonstrated how the declines of the 1980s and 90s had reversed in 16 percent of the aquifer systems the authors had data for.

For a water-stressed country like Saudi Arabia, substantial public and private sector investment has been made into water and desalination infrastructure to create as much usable water as possible.

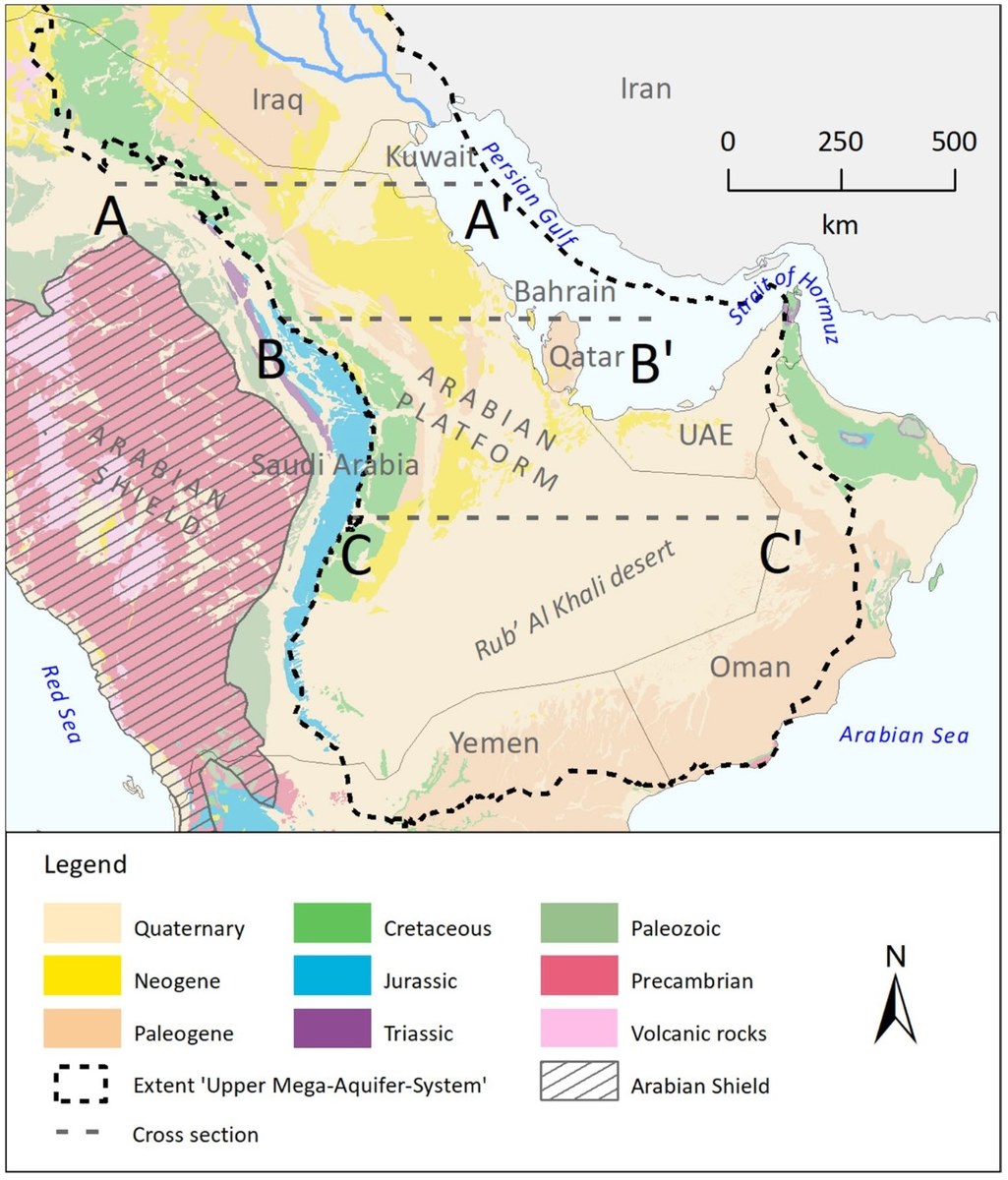

One initiative, bin Dakhil said, is the Upper Mega Aquifer System, which is one of the largest aquifer systems in the world. It underlies the extreme deserts of the Arabian Peninsula and crosses borders between Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Jordan, Oman, Yemen and the UAE.

Simplified geological map of the Arabian Peninsula showing the extent and outcrop of the principal aquifers of the Upper Mega Aquifer System in Saudi Arabia, considered as one of the largest aquifer systems in the world. (Infographic courtesy of the Hydrogeology Journal)

It is built of several bedrock aquifers or sandstone and karstified limestone aquifers that are then imperfectly hydraulically connected to one another. The main ones are the Wasia-Biyadh sandstone aquifer, and the karstified Umm Er Radhuma and Dammam limestone aquifers.

However, due to good water quality and high yield, these aquifers have been intensively exploited, leading to the depletion of groundwater resources.

In central Saudi Arabia, groundwater levels have declined for decades, but evidence is now emerging that these declines are slowing down due to policy changes. Bin Dakhil told Arab News that the amount of water lost from aquifers is now being reduced.

“Secondly, there has been a lessening of the impact from groundwater withdrawal on rates,” he added, emphasizing the major governmental measures and decrees passed to mitigate the challenge of water scarcity.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

The Kingdom has launched the National Water Strategy 2030, prepared according to the principles of integrated water resource management, with aims to restructure the country’s water sector and transform it into a more sustainable and efficient one.

The strategy, bin Dakhil said, involves a variety of initiatives, including ones that call for irrigation efficiency and water-reducing agriculture practices.

Evidence suggests that laws and regulations to prevent or limit diffuse groundwater pollution from agriculture, and especially their enforcement, are “generally weak,” Hoogeveen said.

“Policies addressing water pollution in agriculture should be part of an overarching agriculture and water policy framework at the national, river basin and aquifer scale,” he added.

In terms of groundwater development, rural electrification has been a principal driver, said Hoogeveen, especially where rural power grids have been extended into areas that would otherwise have relied on diesel fuel or wind energy.

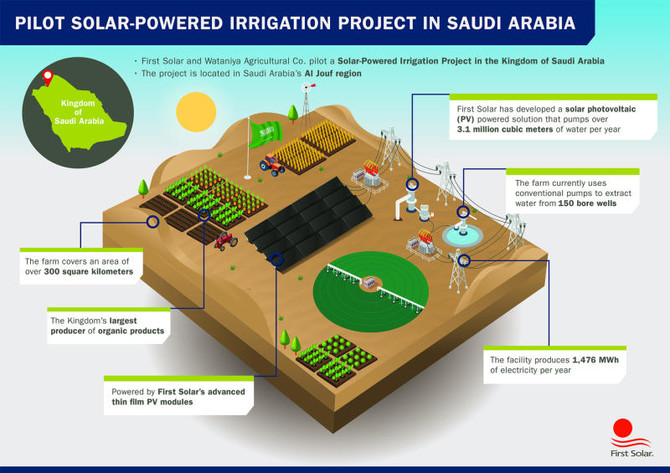

Additionally, advances in solar technology have witnessed the development of solar-powered irrigation systems, adopted at scale to service farming operations.

“However, there is a risk of unsustainable water use if SPIS implementation is not adequately managed and regulated,” he said.

In Saudi Arabia, bin Dakhil said “the deeply rooted use of non-conventional water to mitigate the depletion of non-renewable groundwater by an increased use of renewable water for irrigation.”

CaptionFirst Solar Saudi Arabia and Al Watania Agricultural Company completed a pilot project that uses solar energy to power an irrigation at a farm spread over 300 square kilometers in the Kingdom's northern province of Al Jouf. (Supplied/File)

An example is renewable water that is being pumped from the Dammam region into the agricultural area of Al-Ahsa in Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province through a pipeline with a volume exceeding 200 thousand cubic meters per day by the Saudi Irrigation Organization.

Additionally, technical and legislature governance tools have been put in place that include hundreds of groundwater observation wells augmented by the implementation of water by-laws through licenses, metering of groundwater withdrawal and tracking of drilling rigs using smart technology to monitor and measure water quality, conserve water supplies and enable citizens to function efficiently.

Furthermore, Saudi Arabia is increasing the amount of rainwater harvesting through new dams and efficiently managing existing dams to allocate water to agriculture.

“The Kingdom has also established a center for water efficiency and rationing whose policies target increasing the efficiency of groundwater use and rationing its withdrawals,” said bin Dakhil.

King Fahd Dam, located in Bisha governorate in Asir province, is one of the largest concrete dams in the Middle East. (SPA)

All these measures demonstrate the Kingdom’s steadfast attention to not only its own issues with water scarcity but also the global challenge to use water sustainably.

One of the Kingdom’s main obstacles to achieving sustainable development is the dearth of renewable water resources and the rising demand for water.

With the dedicated measures being taken by both the private and public sectors, the Kingdom has the potential to turn its lack of water into a long-term success story — one that could serve as a model for other countries struggling with water scarcity.